Leah Misemer

October 2015

The following interview was conducted while Nigerian cartoonist Jimga was visiting the University of Wisconsin-Madison in conjunction with his 2015 exhibition “The Change We Need,” which he displayed at Michigan State University and online at Africa Cartoons. On an October afternoon after Jimga gave a talk on cartoon representations of Boko Haram for Africa @ Noon, Leah, a graduate student in the English department and researcher for Africa Cartoons, talked to Jimga about how he became a cartoonist and why he considers cartoons a powerful medium. They also discussed Jimga’s creative process and why he likes posting his cartoons online. Jimga is both a scholar and an artist, and the interview references a paper Jimgah presented at the University of Lagos Research and Conference Fair in 2011 about a project where he analyzed the comments of cartoons he posted on his Facebook page. You can listen to audio of the interview and read the transcript below.

Leah: My first question is how did you become a cartoonist? How did you come to this art that you do?

Jimga: I started drawing at a very tender age. I remember that when I was in early school that we call nursery school, I loved watching cartoons on TV, and I tried to recreate every story that I saw on TV. I would show it to my mom and she would be like, “Wow! It’s good! It’s nice!” She encouraged me a lot. That is in terms of the drawing.

The other aspect is that I imagine things a lot. Sometimes I may just sit down here, and I may be looking at you, but I have gone. I remember when I was in secondary school after primary school, I have a sister and her boyfriend bought me a book, which was Animal Farm by George Orwell. I read the book, and I was so absorbed with the book to the level that I thought it was real. I didn’t know it was a fiction. I started treating animals very, very well, so that in case they would revolt, they would remember me. I tried to illustrate all the scenes in Animal Farm. I will have drawn every episode in that novel. I love it so much. My sister’s boyfriend later saw the drawing, and he was so impressed. He encouraged me. He was in the university then. He was an undergraduate. He told me it was a fiction, that it was a satire to satirize Russian communism. I was like, “Wow! So this is not real? Somebody can just imagine things like this as to be? That means I can use something that is not real to comment on something that is real.” I can say that is how the ideology of cartooning started in me.

It was there, but I did not really develop it until I was in the university at University of Lagos. The second year, we were given an assignment of cartooning, to do something about the political situation. Out of all the assignments that were submitted, the professor brought mine out and said, “Wow! This is great. You are going to be a great cartoonist.” He looked at it and asked me what was I thinking of when I did something like this. I looked at the situation and used different symbols to represent certain things in the society. That was what impressed him.

L: What was the cartoon of? Do you remember?

J: I remember vividly. That was when the president Olusegun Obasanjo was in power. There was a problem. A lot of people believe that even though he came in as a democratically elected president, because he was a military president before, a lot of people believe that he is still dictatorial. They were now trying to evict him from the House of Assembly. That’s what the situation was then. Obasanjo happens to come from Abeokuta in the southwestern part of Nigeria, and it is believed that Obasanjo is a prince and that Obasanjo has magical powers. Several times they’ve tried to kidnap him, they’ve tried to trick him, and it didn’t work out. I drew Obasanjo sitting on a throne with all these magical amulets on his body like a masquerade. I did people trying to pull his leg. The House of Assembly, that is the Senate house was on one side, and the House of Representatives was on the other side. They were pushing him, and he stood there and he was reciting incantations like, “No, nobody can remove me from this seat. It’s not possible.”

To me, it was just a simple thing, but my professor wondered what I was thinking of when I did it. I said, “I just feel that that is the way it is.” And he told me that what made that thing interesting to him is that, in that cartoon you can read so many things about the president. You can see that he is a prince. You can see that he is somebody that doesn’t frown at the use of juju. You can see that he is a military person. And I said, “Really? You can see all that there, sah?” He said, “Yes. Can’t you see this symbol that you use? Can’t you see this symbol that you use? Can’t you see this? Can’t you see that?” That was how I found myself living with my work.

L: It’s amazing that you could put all of that in one panel, in one picture.

J: And it would still look beautiful. That is one lovely thing about cartoons. From that day onward, the professor started calling me “my cartoonist, my cartoonist, my cartoonist” and I would be like, “Let me do another cartoon. Let me do another cartoon. Let me do another cartoon.” That was second year in the university. Three weeks after that particular assignment, I did another cartoon on my own. Not an assignment. I did it about the situation in the country, and I pasted it on the board. I wrote my name there. Some students gathered. They saw it and said, “Wow! This is great!” They laughed. Then I started putting a cartoon out every week, because people were now asking, if I didn’t put a cartoon out, “Jimga, where is your cartoon? We can’t see anything to laugh at today.” They encouraged me by saying that.

There was this particular cartoon that I posted that criticized the president seriously. I remember it was a particular policy, and in my own view I felt that it was not right, and I put my view there in the cartoon. The Dean of Faculty saw the cartoon and ordered people to remove it from the wall. He took it to his office and ordered people to look for me. They called my HOD, Head of Department, and told him to look for me, as well. My department is three departments in one: the visual arts, the creative arts, and music. At that particular time, my HOD was in theatre, and doesn’t know much about visual arts. When they called, my HOD was like, “Okay? What is it? This is fine work.” The dean says, “No this is not fine work. This is school is a federal institution, and this boy is criticizing the president. That means something is wrong. It can’t happen.” My HOD called for my Head of Units, the head of my visual units. When my Head of Units came to the office, she was like, “Well, the boy is expressing his opinion. Is it not true, what the boy is talking about? Don’t we know that this is the truth? The boy has not done anything wrong. That is the way it is.” She basically raved and supported me.

L: It’s crazy that you experienced censorship, or attempts at censorship, that early in your career.

J: Exactly. It was a form of censorship very early. The dean said that I shouldn’t worry, that I can be doing my cartoons, but I should show them to my Head of Units, and my Head of Units should sign first. Do you know the funniest thing? I still have some cartoons signed by my Head of Units, which I kept to show people later in life that I was exposed to censorship early in my career. She was the one that actually stood up for me and said that, “No way. The boy should continue to do his cartoons.” Sometimes when I had a cartoon to do, I would do it, and give it to her, and she would sign.

But later, I may do a particular cartoon and try and change the style. I wouldn’t put my name there, and I would go and paste it. Particularly if the cartoon was very, very strong. If it is about a professor, for example, I would do it and paste it around and be like, “No, it’s not Jimga.” People would say, “Who could have done this?”

L: So you must have developed a range of styles through that practice. You had the this house Jimga style, and then you had these anonymous styles that you were producing.

J: There is also something I wanted to add. I talked about that book earlier. Also, right from my secondary school days, my cousins were in the University of Nevada then. My sister’s friend happens to be the president of the Student Union government. He was an activist. So one way or the other, I became introduced to the concept of activism. Sometimes when they talked and discussed and all that. Then that put me in a kind of situation of trying to express what is around me in a visual form. Not just drawing. Personally, as I am now, I don’t actually like the kind of art that is just merely representational. I believe art should be for life’s sake, not for art’s sake. That’s me. I molded my opinion right from that particular period.

L: Did you work for newspapers during this time?

J: Yeah. Even before I finished school, I was working as a freelancer for an advertising agency. I studied graphic design and illustrations. And from that particular period in time, sometimes I’d get commissioned jobs for illustrations and all that. But I love to express my own creativity, not just to illustrate. I love to comment about the political realities. Way back in 2008, once I would do something, I would put it on Facebook. My friends would comment. And there was a time where I would publish my cartoons in the magazine of Center for Contemporary Art, Lagos. For two years, I published some of my cartoons there.

Later, I worked as a freelance cartoonist, as well, for The Moment newspaper. A senior colleague of mine now, who happens to be a friend, told me that I could get newspapers around to publish my cartoons. I went to some and got a job with a particular one. I did it, I think, once or twice. Then the third one, they were trying to change my work for me. That was how I stopped working permanently. As a person, I don’t actually like anything that affects my expression in terms of cartooning. I hate it. I don’t like it. So once I give my cartoons to a particular publishing house, and they are like, “Ah, no. Can’t I change this?”, I lock the door.

L: You don’t want that kind of censorship. You’re an artist.

J: Exactly. I’m also not keen about the money. My cartoons are not actually really for sale. That is why I don’t think about working permanently for a newspaper. Because of censorship and because of the fact that I don’t about selling my cartoons. I don’t care about that.

L: And that enables you to post your work online in the way you have, which I find really interesting. The project that you did with Facebook, the one that you have posted on your website, that’s such a cool archive of cartoons and responses to cartoons.

J: I collected all the responses. I used sniping tools to collect everything, and I analyzed the comments against the cartoons and all that.

L: Did you find anything particular about the kinds of comments that people were writing? Did you analyze the comments for patterns at all?

J: I analyzed them for patterns, but in the context of the sociopolitical issues in Nigeria at that particular time.

L: Can you give me an example of what that might look like?

J: Most of the cartoons that were posted at that particular time were about the presidential election campaign that was around 2010. I posted some cartoons that were produced between 2008, 2009, and 2010 there on the Facebook page, and people were commenting.

At that particular time, there was a problem within the political system in the sense that Obasanjo came into government through the People’s Democratic Party (PDP). Obasanjo served for 18 years. Then, Obasanjo passed the mantel to Umaru Musa Yar’Adua. There were so many problems, because of the fact that Obasanjo’s Vice President, who happens to be Atiku Abubakar, wanted to succeed him, but Obasanjo did not want that. He believed that Atiku Abubakar was corrupt. Maybe something happened betweeen them. I don’t know. So Obasanjo supported another person entirely, who happens to be Umaru Musa Yar’Adua, and a lot of people correctly pointed out that Umaru Musa Yar’Adua was not actually healthy at that particular time. Obasanjo supported Umaru Musa Yar’Adua and his vice then was Goodluck Jonathan. Goodluck Jonathan comes from the south south part of Nigeria. Obasanjo’s argument for putting Goodluck Jonathan as Umaru Musa Yar’Adua’s vice was that Good Jonathan’s people had never represented Nigeria at that level of government, and people should give them the opportunity. That was how Umaru Musa Yar’Adua and Goodluck Jonathan won the PDP primaries. At that particular period in time, PDP was the dominant party.

Eventually Umaru Musa Yar’Adua won, but two years into his administration he died. There was a serious problem in the sense that some people saw that situation as a kind of machination of Obasanjo to make sure that Jonathan is there. When they saw the whole thing, especially the people from the north, they kept saying, “No, Jonathan can never succeed Yar’Adua.” Why? Because Obasanjo comes from the southwestern part of Nigeria, so now the power should go back to the north, not to the south. The remaining two years that Yar’Adua was supposed to finish, they should take another person from the north. Because of that, a lot of people from the south south now saw the situation as a serious problem, because why should the north think that being in power should be their birthright? In short, the situation created a lot of problems. Jonathan was sworn in amidst a lot of controversy. Jonathan there for two years, and the northern people think that, “Okay. He will be there for two years to finish Yar’Adua’s program. Then, after that they will have to bring somebody from the north. When the two years came, there was a problem because Jonathan wanted to run for being the full president. And the people from the north were like, “No, it’s not possible.” Nigeria was divided along the ethnic line politically. People from the north thought the president should be from the north. There was a kind of sympathy for Jonathan. People would say, “Let this person rule,” and all that.

When I saw the whole thing, I put my cartoons online to fell people’s opinion about what is going on. When people saw my cartoons, they started responding. I was able to analyze their responses to find that a lot of people voted for Jonathan based on sentiment and not because Jonathan was the best choice. That was my prediction and it came to pass.

L: You found that based on these audience responses to your various cartoons that you collected on Facebook? That’s really cool. That’s an interesting finding in terms of how voting works and the role of emotions in the democratic process. I want to shift gears and talk about color now, which you mentioned in your talk earlier today. As someone reading your cartoons, and when I was uploading them on the website, I was struck by their color. They’re so saturated, and there is so much color in them. I want to hear about how you make your color choices. Is that an organic process? Are you trying to represent something when you’re using a specific color? What are you trying to do when you use your color?

J: Some people believe that cartoons should just be in black and white. I see that as a kind of carryover of perception, from the fact that they are used to seeing cartoons in black and white. There is nothing that states that cartoons shouldn’t be in color. Cartoons started to be in black and white because of technical issues: most newspapers were in black and white because it was more expensive to print in color. That is one thing. Because they used to be printed in black and white, some people think the legitimacy of the cartoon is one of monochrome, which I kick against.

The cartoon that I did that was my first cartoon was in color. Way back then. Even though I drew and painted with wash, and all that. The thing is, apart from the message, I also believe that aesthetics are important in any work of art. It is the aesthetics that will actually lure your audience to look at your work. You are drawing them nearer in order to get the message across. That was the first reason. However, I believe that cartoons are not only for aesthetics. They are for utility. Cartooning is a functional art. I don’t think the aesthetics should override the function. When I’m making a cartoon, I’m thinking of the aesthetics, and at the same time, I’m thinking of the utility. That is why you see that my cartoons don’t really conform entirely to the principles of aesthetics in terms of the drawings of the forms. In terms of the forms, sometimes the head may be bigger than the body, sometimes the hands may be longer. It depends on the particular message I want to talk about. That informs the concept of aesthetics that I use for each particular object.

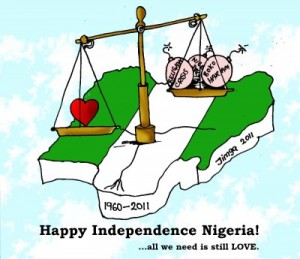

Regarding the choice of colors, I use them symbolically in my works. Even though they are there for aesthetic purposes, they are also functional in the sense that, if I want to represent something—a chaotic situation, for example—in my cartoon, I use colors that are derived from cultural assumptions. There are some colors that represent danger or evil. I use colors for that context. There are ways through which artists can control their audience, and there are ways through which artists limit the understanding of our works to a particular audience. Cartoonists do that a lot. If I’m using a particular color, I don’t want that cartoon to be interactive, per se. I may just use green for something, and that green may be talking about Nigeria. That means I can communicate some things subliminally with my color without all those things being there. Sometimes I may want the audience to think deeper about a particular situation or to reconnect with a particular situation. In order to comment about the contemporary issue, I may look at religious allegories or bring a particular passage in the bible. By doing that, I believe that some of my audience that know about that story will connect with it, while the others that don’t know about the story, I believe the aesthetics must be there for them to enjoy. In a nutshell, I use my color symbolically for aesthetics and also for functionality.

L: Part of the efficiency of the image comes from the color. You can get so many ideas into this one panel and one of the ways you do that is with the symbolic color.

J: The fact that you have limited space to talk about so many things means you have to use colors to complement, as well, in order to talk about the ideas.

L: You mentioned a bit about the process in talking about color, but can you tell me more about how you make your cartoons? I know you do it digitally now at least. What kind of software do you use? Do you use a tablet? I know a lot of webcomics artists use tablets now. I’m curious about your process.

J: What I usually do is, first, I sketch my cartoons on paper or cardboard using a pencil. I sketch using a pencil, then I trace the pencil with a pen. After that, I scan into the system and put the image into Photoshop. I paint in Photoshop. After that, I take the image into CorelDRAW or Adobe Illustrator and add the textual elements there. After doing that, I can then export to Facebook. I’ll have an image that has a higher resolution and ones that have lower resolutions.

L: The digital is more a matter of the sharing aspect for you than anything else. Do you feel like digital tools give you opportunities you don’t necessarily have with your pencil and your cardboard?

J: It does. I believe that art should be democratized in the sense that a lot of people should see my work. Some people believe that if you post your cartoons on Facebook people will just print it without giving you money. I tell them I don’t care. Inasmuch as this is my idea and my idea is actually influencing somebody somewhere, I’m fulfilled. That is what I love. I see the digital format as a very significant tool in achieving that aim of spreading the gospel, to make sure that my work gets to as many people as possible. If I were just drawing on paper with traditional media, it won’t be that easy for a lot of people to see my work. And if a lot of people don’t see my work, how can I say that I’m an activist for society? That would mean I’m not actually playing my role, because I believe that artists should be concerned about the situation in the society. And traditionally, that is the artist’s job, right from inception. Especially the cartoonist. We are like the watchdogs of the society. When we feel that something is not going on well, we put it in the cartoon and make sure that as many people as possible get to see it. You may not actually realize that there will be somebody somewhere who may have other forms of making sure that what you are thinking of in that particular is being implemented. The person may be more powerful in terms of making sure policy can be implemented, but that person may not know there’s a problem until that cartoon gets to him.

L: And the way it gets to them is through this digital form. I think about some of the underground cartoonists from the 1970s in America that I talk about in my own work. They were dependent on the print format, because the Internet didn’t exist yet, and they talk about how their audience was limited by who would go into these stores where the comics were sold. What did you do before the digital? How did you get your work out there before the digital? I guess you had the newspapers, but then you stopped working for the newspapers.

J: Through the newspaper, first. But also, I cannot really say that they were getting out when I was in school. That zeal to make sure that my work gets out made me do my work. I would do extra photocopies, and I would paste on the notice boards around the school. I was not concerned about getting paid for it. I was concerned about my commentary, about my perspective, and how other people could take that to influence the society. Luckily for me, I’m one of the few that got ahold of the digital medium earlier. Once I knew I could do this digitally, I just started straight away. Even the cartoons I was sending to newspapers then, I was doing digitally. I’d send the cartoon to them and put it on Facebook, as well. I’ve always said that the cartoonist should be the copyright owner of any cartoon. I don’t want a situation whereby a particular newspaper publishes my cartoon and I can’t publish it anywhere else I want. I don’t believe in holding knowledge, because you don’t know whether there’s another person that can take it to another level that you couldn’t even think of. So right from the beginning, I’ve been using digital media.

L: My last question has to do with your exhibition that we’re featuring on the website and that is available at Michigan State right now, “The Change We Need.” I wanted to ask you a little bit about this aspirational element of cartoons, the idea that they can show us both what is happening in society through this idea of framing that you’ve talked about and also this idea that cartoons can show us what society could be. The latter seems to be what you’re trying to do with this exhibition. I was wondering if you could talk about why you have chosen cartoons for this kind of aspiration. Aside from the idea of efficiency that you talked about earlier, why not write a book? Or a pamphlet? Why draw cartoons, if you want to change society?

J: First, I’m an artist, and that is my tool. I believe that everybody in society is blessed one way or the other with a particular means of reaching out. Poetry, literary, visual, verbal, and all that. My own ability, or talent, is the visual arts. That is the first thing.

Another thing is that I love the fact that it is the visual arts because of the fact that the visual arts, to me, is actually magical. In terms of attention, it is highly magical. For example, what is written in a book can actually be summarized within just one plate of visual form. That is one thing. The ambiguity of visual arts is another part that I love. You can say that they are a reflection of what happens in the society. You can have another interpretation. If a hundred people look at the same work, they will have a hundred interpretations of the same work. That is the beauty of the visual arts, unlike something that is written, where this is black. Because it’s written, we know that it is black and it can be nothing else. But with the visual arts, there’s ambiguity in the expression, and that is the magical power that they possess. That is one of the reasons why I love visual art, because it can be interpreted so many ways. That is also one of visual art’s shortcomings, one of the problems it can create in society, but that makes it powerful. Don’t forget that not everybody is literate.

Going back, cartoons have played a significant role in spreading or passing out information about so many things in society to everybody. During the Reformation period, when the church was being reformed, Martin Luther engaged the work of cartoonists to satirize the excesses of the Pope and the papacy in order to convince the people that there should be a reformation. That was during the Protestant period. If you see the cartoons that they did then, they equate the Pope with the devil in order to bring about a new world order. Martin Luther found the use of cartooning so powerful, even more than the written words he was writing in the pamphlets that he shared. People were easily able to relate to the imagery: “Oh, this shows the Pope as the devil. We don’t want the devil in power.” The power of imagery can easily summarize so many things.

Another thing is that our minds have been configured to retain imagery more. Maybe because of the fact that I’m an artist, my mind retains visual imagery faster than what I read. In fact, if I read something, I transform it into a mental image in my mind. Then I won’t forget about it. That means as you are reading a storybook, your mind is having a mental image of the story you are reading. Our mind processes images faster than words. Therefore, there’s power in imagery. So I love using imagery.

L: It’s interesting how you relate that to the power of art, because some of what you’re talking about in terms of ambiguity, I would argue is also present in verbal art, which I’ve seen, as someone from a literature field. But, I think the ambiguity combined with the power of images that you’re talking about, that is a very convincing message in terms of the power of cartoons.